Code Layout

- Adopting Markup Underneath The Code

- An IDE Utilizes Helper Gadgets to Make Plain Text Usable

- A Central Chore of Programming Is Laying Out Containers

- Some Reasons That Code Has Not Become Completely GUI-Based

- Plain Text Code Is Characterized by Ambiguity

- Plain Text Code Flows Vertically

- Project Maps / Plans

- The Command Line Shell Needs a GUI-Oriented Upgrade, Comparable to Wolfram Language

- Code Layout Features Will Add Power to Plain Text Programming

Last updated on 10-16-22.

Adopting Markup Underneath The Code

There Is No Markup inside a Code File, But There Is No Technical Reason for That

At the current time, computer code is not rendered according to any markup, and this applies to basically any programming language in active use. The code is just listed out line by line inside the code editor as the plain text characters it is. Redesign.Codes recommends changing this such that all future code editors render their code files (inside the code viewer area) according to the files' underlying markup, and XML is chosen as the file format because it is the foundation of SVG (which actually stems from Adobe's proposed file format, PGML.).

Anything in a code file today could have its contents wrapped in a markup format (like XML), from loops to conditional expressions. The file could sit on the hard drive as XML and then be rendered in the code editor, thereby providing a great deal of graphical differentiation between its elements. Many opportunities for advancing code as a whole will emerge.

There really is no reason to avoid converting programming language code files to XML or another markup format. That's because with a rendered result the code could be made to show up any way desired. A code editor can even take markup and render the code exactly the same as it looks today-- if that were ever wanted (though it certainly won't be).

There are a lot of code editors out there these days, but none actually deal with rendering XML for code itself. After this change is made, you could display and edit code any way you want, and the constant need to maintain indentations, a vestige of the computer terminal past, could be left behind. It's important to start removing these invisible nuisances, such as the manual maintainenance of text indentations, and markup is the first step to take because it expands what a code file can provide in many areas.

Markup Enables Interactivity inside Code

When there is markup inside the code file, and the code editor acts as a graphical processor of that markup, there is the ability to add interactivity. You will be able to set an array variable equal to an interactive data table or list. What is future computer programming? You will be able to define interactive controls for any type of object variable that you make in your code: if you make an animation curve object class, you will be able to tell the code editor that you want to edit all such objects with curve interactive controls. Every time an animation curve appears in your code, you will be able to edit it according to what you want, probably an editable graph.

For the programming topic of a data list, we made it fast for you below because, after hovering over a field, you can just start typing over what is there. It shows that GUI can be integrated into computer code without causing trouble for the professional coder. Once this type of example is extended, a set of workflows and states will actually be able to be utilized in code files for the first time.

| var | warehouseStates[] | = |

|

Markup Inside a Code File Informs the Code Editor

Also, if you typed out a variable and it didn't exist, the code editor would know right away because of parsing the XML. If our code had markup underneath it wouldn't have to allow any syntax errors or any typos before code compilation. Your code could compile nearly 100% of the time. That's because anywhere the text cursor were deposited inside the text, the code editor would know what is allowed (based on its existing trees that describe the programming language's syntax). And if the text cursor left the location without depositing valid code, the code editor could just ignore what was entered.

It is the possibility of integrating non-code aspects of the software (e.g. images, curves, 3d models) within the code document that should take computer code to an advanced level. Not only will the underlying XML allow for the addition of these elements inside code, but it will allow for multi-column layouts found in a magazine or other print publication.

On the code layout side of modernizing computer code, here are four important components to start with:- Markup Inside The Code File Format

- Implementation of Page Layout by the Code Editor (Multicolumn)

- Interface Controls for Objects (e.g. Data Tables Like The Example Above)

- Brisk Mouse + Keyboard Interactivity with the Code Elements (Going Beyond Just Typing) On the graphic design side of revamping computer code, here are some additions:

-

Every variable displays a small symbol of its data type next to it, and all object

classes are provided symbols automatically if they were not provided by the programmer in advance.

For example, a bezier path will have a pen symbol next to it, a rectangle struct will have a dotted rectangle next to it:

rectangleBezierPath.appendRect(⬚

rect);

rectangleBezierPath.appendRect(⬚

rect);

- Every container made with curly braces is replaced with an outlined box, and the GUI interactivity makes this as fast as removing or replacing curly braces.

-

When there are indentations, they are made graphically distinct. An example using

curly braces is below.

Writing a Line of Code Next to an Image or 3D Model Will Require Implementing Magazine-Style Layouts

When making an app, the programmer places any media "assets" (images, 3d models, sound files, etc.) into separate file directories. The media files are totally separated from the code files that make use of them. That is to say, an image file will only be viewed by the programmer if he goes out of his way to navigate to it inside the IDE, interrupting the rest of his programming. This leads to heavier reliance on multiple computer displays, to open up windows and multiple frames inside windows. It also requires frequent interaction with the IDE interface so that anything referenced on a line of code can also be inspected.

What the programmer should really want is the ability to write code that sits alongside, above, or below the image assets, laid out magazine-style. A magazine-style layout of code also allows for programmatically tapping into the various properties that the media files carry, using connector lilnes, making use of them as variables or objects inside the code.

For example, it would be far superior to interact with an animation curve graph inside a code file, as an interactive element compared to typing out all of the code needed to make a specific, predefined curve. And if the IDE or system provides this stock, interactive utility it will be used by all programmers for all sorts of purposes.

Utility elements such as graphs can be inserted into code, but the file format for programming has to change to one that embodies markup.

When programming languages were first produced, computers did not display bitmap images or interactive media except in special research project circumstances. Today, though, this is a main part of what people use the computer for, and programmers are often programming something that intersects with graphics, at least the GUI. The form of code that programmers use today, as a whole, does not adequately reflect what they are engineering it to do.

Editing Code Interactively in AR/VR Is Made Closer to Viable as a Work Activity When Code Uses Markup Underneath

Because of the markup being provided, 3D programmers will have handles on the code that is shown in a code editor on a desktop computer. It will be easy to take the code and pop it out into 3D.

Two Steps to Upgrading Computer Code

There are two initial steps to upgrading today's computer code, to set programming on a more advanced technological course.

The first step is to replace the plain text format with markup so as to add structure and hierarchy to code files, which will then enable a broad range of features inside programming languages. The second step is to decide how the user interface will exist once the programming language adopts new functionality enabled by markup. For example, if there is rich text or mathematical notation, what interactive convention does the IDE use for insertion or editing of the text? The window for editing a code file may end up taking on the appearance of a vector-drawing program or page layout program, but it must match the speed of interaction programmers currently have with plain text code. That is the top priority after implementing markup. Interface slowdown has prevented code from upgrading to a more graphical form. If the mouse is to be utilized in a new interactive scheme for programming, it should not be done until a demo'ed scheme matches current interface speeds. A way to ensure this is by keeping programming keyboard-driven during use of the mouse. Another avenue involves providing the programmer specialized programming peripherals, with multiple sliders and macro keys, but these might have to be carried inside laptop bags.

The Benefits of Markup Will Be Numerous

Markup will allow the incorporation of many modern computing features into code, such as page layout, rich text, mathematical notation, geometric figures, graphing of equations, hyperlinks, images, and data tables. With markup, connector lines can be drawn between elements inside a mostly text code file, for whatever programmatic purpose that is needed, and this points to how a new landscape is opened up in terms of capability.

There isn't a mainstream programming language that couldn't be converted to a markup format underneath, but then new dilemmas will appear: with the new features enabled by markup there will be consequent user interface needs.

How code is displayed in a version control (e.g. git) repository web page will have to be accommodated, but this also should not be too difficult to handle given that it is markup being added. For some people, the terminal shell will also need the capability of displaying the marked-up code files-- but this is also an upgrade that is long overdue anyway. There is no real reason that shells should remain in plain text, as there isn't a computer manufactured today that is technologically limited to that, as was the case in the early 1990s.

The User Interface in Plain Text

A mechanical typewriter, of course, does not carry any kind of capability to manipulate what was just typed on the page, nor does it allow any subsequent selection of the text like we see in a GUI.

Therefore, there is indeed a user interface scheme already existing in plain text computer code, which has always been there, but this situation is usually not interpreted this way, because interface is usually only acknowledged at the moment a GUI appears. The user interface for plain text code exists and is substantially real: it is simply the setup of a typewriter keyboard combined with the computer's editing (backspace, undo) or GUI conventions of selecting text and moving it around, either through keyboard commands or mouse.

An IDE Utilizes Helper Gadgets to Make Plain Text Usable

The computer industry has run up against a wall: the raw text file format, present in computing since the beginning of typewritten code, lacks outlets for growing software development needs. Today's processors are, without exaggeration, thousands of times faster in clock speed than they were in 1972, when the C programming language was introduced.

Today there are 4K video editors, music composition programs, 3D modeling and animation packages, and artificial intelligence applications. A variety of sophisticated, demanding software categories— not present in the 70s and 80s— are taking computer science's plain text dogmatism to its absolute limits.

To keep up with this challenging environment, today's code editors (IDEs) are performing cartwheels to ensure that plain text remains usable:

- They implement code completion GUI boxes that appear as a person is typing.

- They actively color keywords, to make improvements in readability. (There are no colors inherent to plain text).

- They draw vertical lines through the plain text indentations to add minor layout features (Visual Studio does this, with Xcode providing code "ribbons").

- They intervene when the tab key, parentheses keys, and curly brace keys are pressed, to provide interactive formatting that is not naturally present in the plain text format.

- They provide miniature maps for viewing the currently opened file, so that programmers know what section they are working in. (This is using image processing to capture, scale, and render a screenshot of the plain text).

- They present accessory windows that offer draggable, premade code snippets and templates. (Drag-and-drop is a convention of the GUI).

With all of this added IDE functionality, is this really programming with plain text anymore?

Plain text is surrounded with a lot of helper gadgets to make modern programming work. Only a tiny minority of programmers prefer the raw text editor to an IDE for professional software jobs.

New features added to IDEs are usually just reactions to the inadequacies of raw text, the inherited medium for code.

To see the difference between this unconscious process and what would be an intentional plan or design, here is some functionality that you can find in any word processing document, but which is missing from (and would be of value to) an IDE:

- Section headings, subheadings, and horizontal line dividers.

- Layout tools for arranging information on a grid or table.

- The embedment of images, sound, or movie files, for explanations.

- Hyperlinks, to allow immediate navigation to another, relevant part of the document.

- Diagramming tools, using vector graphics, to explain procedures.

Shouldn't commercial software development contain this much functionality— as much as is found in a word processing document

or spreadsheet? Instead, it is as if we are all stuck in the 1980s, typing in the most crude way to

embed our comments (// and /* */) in code.

So much programming time is spent tossing around opening and closing characters, using the tab key to make the resulting containers look tidy.

A Central Chore of Programming Is Laying Out Containers

In nearly all programming circumstances, there is an enclosure of some sort:- Brackets (

[ ]) serve as the borders for an array. - Parentheses (

()) enclose the contents of a computation. - Curly braces (

{ }) define the boundaries of execution statements. - Comment block (

/* */) characters envelope non-executed text. - Quotation marks (

" ") surround text characters and strings.

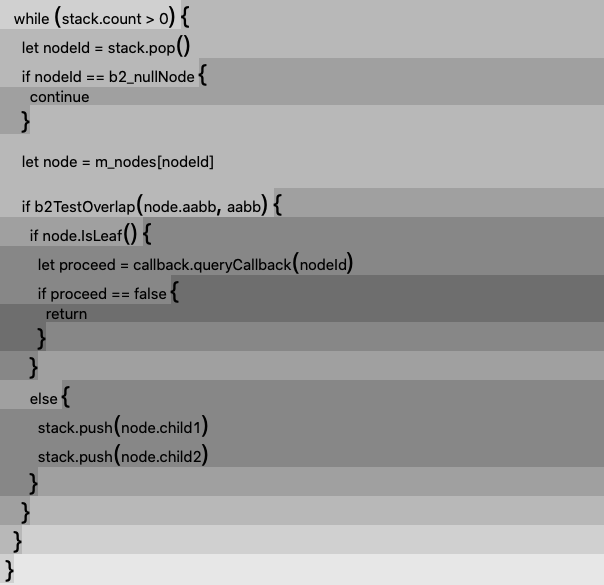

These characters are often just substitutes for what would be drawn on paper as graphical enclosures, such as a rectangle. To illustrate below, we have taken a function and colored the background of each major subcontainer. We have also increased the size of curly braces and parentheses. The purpose is to show how much clearer programming would be if some amount of graphic design were applied.

It sure would be nice if IDEs colored the backgrounds of containers this way. It would make

code a lot more manageable. The if statements were given

helpful contrast by increasing the purple saturation with each nesting. The viewer can easily distinguish them from the while looping statement (in which they sit) because of its green background. Orange is reserved for function bodies. In this way, a programmer

can see immediately what a page of code is about without needing to dig into it.

Placing Layout Commands inside The Comments

Here is a proposed method for embedding layout features into a file of code without changing anything about the code itself: put layout commands inside the comments (//) for the IDE to handle.

We take cosmetic improvements to a higher level in the example below, hiding the curly braces completely with

a new command, --CONTAINERIZE_FOR, which

graphically encapsulates all for loop statements present

in the file. There are two for loops, one nested inside the other.

// --CONTAINERIZE_FOR

//

for

(int i = 0; i < cols; i++)

// Loop for column index.

for

(int j = 0; j < rows; j++)

// Loop for row index.

int x = i * rectWidth;

int y = j * rectHeight;

fill(125);

stroke(0);

rect(x, y, rectWidth, rectHeight);

That is so much better than a bunch of curly braces strewn all over

the place. And if it were applied to other sorts of statements, like switch

and if-else, the readability of code would improve.

Yet, we made this transformation take place inside standard plain text code comments; if we remove the command, we will get our old plain text setup back (under this proposed scheme).

Layout Commands for Better Use of Screen Space

Here is some screen footage of someone writing code on a widescreen display. The right half of the screen remains completely empty.

(unused portion of a modern widescreen display.)

What can be done about this? Instruct the IDE to set up functions side by side. This is a feature that has never been provided in any IDE.

The --TABULARIZE_START command tabularizes, or puts into a table, what sits between it and the --TABULARIZE_END statement.

// --TABULARIZE_START

func makeRectangle()

{

// try editing here.

}

func makeCircle()

{

// try editing here.

}

// Functions written in this area

// should be automatically appended

// to the table by the IDE.

// --TABULARIZE_ENDLong lists of variables can finally be placed into tables, making use of multiple columns and rows. It is the IDE that would take care of the tabularization of the code, according to the commands put in place.

// --TABULARIZE_START

var arrayOfRectangles = [];

var arrayOfCircles = [];

var arrayOfTriangles = [];

var arrayOfPentagons = [];

var arrayOfHexagons = [];

var arrayOfSeptagons = [];

var arrayOfOctagons = [];

var arrayOfNonagons = [];

var arrayOfDecagons = [];

// Variables written in this area

// should be automatically appended

// to the table by the IDE.

// --TABULARIZE_ENDIf this were applied to an entire document of code, the vertical span of the document, the amount you need to scroll through, would be reduced by at least ½.

More examples of this layout method are in the sections Plain Text Code Flows Vertically and Code Layout Features Will Add Power to Plain Text Programming on this page.

Some Reasons That Code Has Not Become Completely GUI-Based

In the past, all attempts to advance the appearance of code required the adoption of a new paradigm, such as visual node-based programming, where patches or nodes are dragged around and linked together.

There are some issues with graphically-driven programming languages, though:

1. The mouse doesn't cut it (until it is modified for improved interactivity).

Media production professionals opt for keyboard shortcuts in their daily use of high-end video editing and photo editing software, instead of always clicking menus with the cursor. The keyboard is more powerful than the mouse in rote circumstances, and just like video editing, computer programming entails a lot of rote tasks.

A keyboard sold to users of the Maya 3D modeling program. Without a keyboard to change the current application mode, the cursor can only click things.

Most programmers use the mouse to scroll through the document with the scroll wheel. Or, with the click button, they use it to reposition the text cursor.

It would be nice if programming in the future followed the interactive approach of a media production application, such as a vector editor or 3D modeler, because these applications modify the cursor's state, constantly. They make the mouse do different things, with the use of various keyboard keys.

A cursor without additional modes is too limited for building up intricate bodies of code. That is what a person encounters with node-based programming.

Clicking inside tiny circles and then dragging lines isn't going to work for the future of programming. The keyboard needs to play a role, at the same time.

2. Variables and functions can be interwoven in plain text, which is not available in other programming schemes.

Plain text programming is also more capable because it allows combining functions and variables together in tightly-integrated ways, line by line. A function can contain a variable, which was just modified by a different function, and this can happen in just a few lines. This may not be the only way to program a computer, but it has no equivalent in node/patch-based programming.

Plain text has remained the only viable medium for writing complex, large-scale code for this reason.

This is not to say, however, that an IDE should never incorporate nodes or other GUI controls next to plain text. In fact, that is a suggestion of this page, that there should be more interaction between the two, in a way that does not infringe on existing software practices.

Plain Text Code Is Characterized by Ambiguity

Code is much more tedious to deal with than it seems, and this is related to how large amounts of programming language functionality have been squeezed into the plain text format as decades have passed. Syntax is often made fuzzy because programmers are asked to do too much with the raw text format.

Earlier, we increased the size of parentheses and curly braces. That is because in plain text, the individual characters do not stand out when they should. Reading complex code is often hindered by the total lack of graphical distinctions.

1. There is frequent reuse of the same character for unrelated purposes.

Because of the limited provision of characters on standard keyboards, there is frequent reutilization of a given character. Often it takes some work to figure out what is going on in any area of code.

- A given curly brace (

})might belong to aclass, astruct, afunction, anifconditional branch, or aforlooping statement, and these are all mixed together throughout any given code file.

⇨ Make the IDE render alternative unicode braces (e.g. 〘 〙 and 〖 〗 ) according to the body area.

if (objectIsShown) 〘 for(int i = 0; i < 30; i++) 〖 print(i); 〗 〙 - The asterisk character (

*) is used to signify the multiplication operator, but also the pointer data type. It also is found at the beginning or end of a comment block (in combination with forward slash).

⇨ Make the IDE render comment block asterisks as bullets (

/• comments •/).⇨ Make the IDE render multiplication asterisks as multiplication signs (

5 × numberOfRows). - Parentheses may serve to enclose a boolean expression, separate parts of a numeric calculation, or declare the signature of a function and its parameters.

-

Chaotic: a programmer might be using parentheses to enclose a calculation inside the parentheses of a called function,

e.g.computeA( (5 + 2) ), making it difficult to see which parenthesis belongs to which part.

⇨ For calculations and conditional expressions, use oversized parentheses, then diminish the size of the parentheses at each nesting level. Optionally, darken the background color as well.

computeA(5 *(3.4 *(var1 * var4) + (var2 / var3) )) -

Chaotic: a programmer might be using parentheses to enclose a calculation inside the parentheses of a called function,

2. Terminating characters such as } do not provide any information about what they just terminated.

Present in all programming languages— but especially apparent in HTML, with closing div tags—

is that the terminating characters do not say what they belong to. If you browse through an HTML document,

what does a given terminating div tag terminate? You don't know at first glance. In regular programming, what does any given curly brace terminate?

To find out, you must scroll up and scan the document, sometimes meticulously.

⇨ Transition to graphical, rectangle enclosures away

from individual characters as the demarcation for containers.

In circumstances where it isn't desired, make the IDE display a label at the end of each terminating curly brace to

indicate what it belongs to, e.g.: } end of class TrianglePath .

3. When glancing at a variable name, the data type may not be apparent.

- A variable is usually declared with its data type next to it. But a problem occurs after this. When the variable is made use of at any point in the future, it has no accompanying indicator of what it is. Three strategies are often used:

- Name the variable with the data type in the name (e.g.

arrayOfRectangles). - Leave out the data type's name in the variable name and rely on the context of the its use to indicate what it is.

- Rely on the variable's name (e.g.

count) to indicate what it is because it would only belong to one data type (integer).

- Name the variable with the data type in the name (e.g.

⇨ Implement the use of symbols next to variables, indicating type.

Below, the IDE adds a pen symbol beside bezier paths.

// Make the rect (this is a struct)

var rect = MakeRect(0,0,100,100);

// Create the bezier path object

var  rectangle = BezierPath();

// use the rect struct to add points to the bezier path

rectangle = BezierPath();

// use the rect struct to add points to the bezier path

rectangle.appendRect(rect);

rectangle.appendRect(rect);

4. When most of the code is out of view, it leaves a person without bearings.

In especially long documents, code still must be edited within a small window frame, with the majority of the code cropped out. Many people orient their monitors vertically in response to this, to put a larger portion of a code file onscreen.

Had code, at any point, taken on the appearance of a blueprint or schematics document instead, this would not be a significant issue, as multiple levels of map scale could be displayed simultaneously, next to each other.

A major constraint imposed on programmers is that code can only be written inside a single column.

To see this for yourself, take some code that you have written and paste it into a word processor, then center-align it.

When code is made center-aligned, it becomes apparent that software developers spend their days traversing a single column of text.

Today's confining, vertical flow of computer code is not the result of some grand design for programming; it is a by-product of the 1970s.

In electronic schematics, by contrast, graphical elements will span both the x and y axes.

For now, until conditions change to allow a complete overhaul of the state of programming, we should take advantage of the IDE to deliberately upgrade the appearance of this very raw programming setup.

Below is another example of the Redesign.Codes method for enhancing source code. It was discussed in an earlier section with the graphically-encapsulated The vertical flow of code can be reined in with the use of tab views.

The three shape-making functions above, which must follow one another sequentially from top to bottom in plain text, can now be placed into a tab view.

We show the functions in their normal, left-aligned state, with a line

of code placed inside each one:

We can make better use of screen space by transforming this vertical arrangement of functions into a tab view.

A programmer can surround some functions with the

As mentioned, even though these are tab views, everything in the code file is still plain text on the hard drive; it is the IDE injecting the presentation into its own windows.

The scroll wheel, which was previously used to scroll down the document,

can instead be used to switch between tabs with a flick, preserving the original user interaction style of the IDE. Conventionally, tab views display only

a single row of tabs. But if a tab view were given two

rows, this would significantly reduce the rendered vertical span of a code file.

The first benefit of these tab views is that code can be navigated

swiftly, and a text file is greatly compacted for viewing. But,

also, it provides opportunites for improved organization. You can create your own tab names

to group your variables or functions together.

Below, there are six variables that are part of a preferences window for an application. The first three The result of the custom tab commands above is the tab view below. Related variables have just been grouped together, producing

a software engineering setup that definitely surpasses the primitive state of

programming in text files.

If five functions have been added to a tab view, and they are of

approximately the same vertical span, the tab view will have reduced that

portion of the document to around 1/5 of its original vertical length.

Furthermore, if tab views are created for many sections of the document,

a software project will take on an entirely different, open feel, one

that is easy to traverse, inspect, and edit.

Plain Text Code Flows Vertically

func makeRectangle()

{

}

func makeCircle()

{

}

func makeTriangle()

{

}Place Tab Views inside Plain Text to Organize and Compact Code

for loops.

As described, it adds UI elements to code through the use of comments ("//"). The comments contain instructions for the IDE to inject UI into the plain text document.

func makeRectangle()

{

// make a rectangle.

var rectangle = RectangleShape();

}

func makeCircle()

{

// make a circle.

var circle = CircleShape();

}

func makeTriangle()

{

// make a triangle.

var triangle = TriangleShape();

}

--TABIFY_START and

--TABIFY_END IDE commands. The obliging IDE then lays them out as tabs.

// --TABIFY_START

{

// make a rectangle.

var rectangle = RectangleShape();

}{

// make a circle.

var circle = CircleShape();

}{

// make a triangle.

var triangle = TriangleShape();

}

// --TABIFY_END

Custom Tab Views Provide Unprecedented Organization Capabilities for Plain Text Code

float variables were made to be edited by the second three TextField objects.

// --TABIFY_START

// --TAB_START:Preferences Window Variables

var defaultFontSizePt = 14.0;

var documentWidthPt = 612.0;

var documentHeightPt = 792.0;

// --TAB_END

// --TAB_START:Preferences Window Controls

var fontSizeTextField = TextField();

var widthTextField = TextField();

var heightTextField = TextField();

// --TAB_END

// --TABIFY_END

// --TABIFY_START

var defaultFontSizePt = 14.0;

var documentWidthPt = 612.0;

var documentHeightPt = 792.0;

var fontSizeTextField = TextField();

var widthTextField = TextField();

var heightTextField = TextField();

// --TABIFY_END

Tab Views Injected into Plain Text Code Will Be of Immense Value

Project Maps / Plans

Find Out How a Project Fits Together By Looking at Its Plan

When the IDE project folder holds the source code for a fully-featured software application, with dozens of files stored inside dozens of directories, accompanied by all sorts of image assets, a problem emerges right away for the newcomer: this is unknown territory, and you may need some time to sort out what all of the files are about and how they relate to each other. To become familiar with the project, you may end up tweaking variables and settings in various code files, then recompiling to see the results.

You wouldn't have to do so much investigative work if you were provided a map, though. Normally when entering unknown territory, be it a nature park or a shopping mall, you will be provided a map.

Currently, what serves as a project map for you is the filesystem (the files listed in the IDE), or, in the best case, an introduction page that gives a thorough summary. For well-established projects, there is also documentation, but reading documentation is not the same as looking at map. Maps provide an overview and can explain how all of the pieces fit together.

The shopping mall map above, although it describes a physical space, does a good job balancing small details with large outlines. Perhaps where you see store names you would find function and variable names. User interface file thumbnails also would have a place next to them. Importantly, it is possible on the shopping mall map to draw attention to individual details with the use of arrows, as shown for the shopping mall information center. So, if the project supervisor wishes to emphasize certain aspects of a project for new contributors, this can be done. It can also be made to function like a massively zoomable map, similar to how draftsmen navigate CAD files.

Even many video games provide maps for their players, especially role-playing video games. If the video game tells the player to collect useful items or perform tasks, the player will pull down the virtual map to find out where his character is located in the virtual world. So, a map is important when the territory is diverse, virtual, and contains many chores, and source code is no different.

Redesign.Codes proposes that IDEs incorporate standard use of a map file, with every created project. (This can be an SVG file underneath to start.) Its purpose is to provide an immediate hierarchy of the project's components, allowing a person to grasp the general structure of the project, and also to provide clickable boxes that take the person to the part of the project that is of interest. It would carry an appearance much like the shopping mall map above. The mall map can be used quickly by any mall visitor because different areas of the mall have been color-coded. This is what distinguishes it from a floor plan.

Start with Auto-Generated Project Maps, Then Provide Customization Tools

It isn't the job of the programmer to be making maps. Therefore, this type of map can at first be automatically generated based on file directory listings (in a layout similar to a tree map) and file contents, but user-customized after it is generated. That is, the IDE will generate these sorts of maps for you to customize yourself, and any files that are added later will be tracked, as the map should update itself as the project changes. The initial generation of the map matches best what would look good without any customization. On this topic, it would be good to look at floor plan software, which provides users premade objects for designing the overhead view of houses. Notably, it is possible to view the floor plan in three dimensions and add 3D objects to it, which might be of value for especially large software projects.

An IDE's project map editor would benefit by looking at features found in residential floor planning software, including the various premade objects.

A Project Map Will Reduce Dependence on File Listings for Navigation

The IDE's window that displays the project map can be left open at all times (perhaps on a separate monitor), allowing for ready browsing of the project. Files that are currently opened would be indicated as such on the map, and clicking on an element that is already open would just bring that tab or window to the front.

This type of setup would allow the layout of a software project to sit on the touchscreen of a nearby tablet computer, too, providing all of the regular pinch and zoom gestures.

Maintain a Separate Project Map for Version Control Repositories

Also of importance are the implications of a project map for an organization's software development coordinative needs. We are all familiar with version control changes appearing with the individual's name beside the most recent change in the file. But, it makes sense also to create a live repository map resembling the shopping mall map, then update information next to the various geographic regions of code. Certain regions of the map can be assigned to specific individuals, with their names next to their assigned areas, and this will make the task of managing and working on a group project much smoother.

The Command Line Shell Needs a GUI-Oriented Upgrade, Comparable to Wolfram Language

The command line is the implementation of a 1970s UNIX terminal. When graphical computers arrived, was brought over to their bitmap displays with no modification from the 1970s. On today's MacOS, for example, the way to access a command line is to launch the "Terminal" app. But what was a terminal back in the 1970s and 1980s? They were computer monitors, given no computing processing power of their own, that acted as gateways to the mainframe computer. The keyboard commands would travel through the terminal machine to the mainframe computer. Contrary to what a lot of people think, many conventions of computing remain the same from decade to decade, even very old ones.

The terminal monitors on which the command line was implemented had no capacity for displaying graphics. It's ok to modernize our command line apps. For example, you should be able to generate a graphic inside the command line and have the graphic show up in a frame inside the terminal app. Then you should be able to do additional operations on that output if needed.

What Wolfram has done with the Wolfram Language, the integration of plain text commands with graphical output, and the ability to continue to operate on the output, shows the importance of integrating GUI features into the common UNIX shell. But it should not stop there. All programs that link into the shell should make use of an established pool of commands, so that the user has an easy guess about how to do something before looking up the specifics.

The Command Line as Swiss Army Knife

The command line isn't as powerful as people make it out to be. If it were, it could do basic things right away.

Who denies that it should be able to take a (dragged) QR Code graphic and decipher the output for the user, as part of a base set of functionality? It should be able to generate a QR Code and actually show that QR Code.

What does it take to make a rectangle graphic, of ratio 16:10 with a width of 15 inches? You should be able to do this in a terminal window, right away, and see the results in the window. But terminals are never providing graphical features today, even though the rest of the computer is. Moreover, whenever there is a program that can run inside the terminal, it doesn't tie into an "umbrella" terminal scheme that has a pre-established a set of functions and practices, but instead it carries out its own conventions independently, with its own arguments and flags.

For every terminal command, you must look up the specific arguments and flags. Usually it is a one shot command, not interactive. The terminal program asks for a sequence of arguments, the return key is pressed, and the output is made, directly to the filesystem or screen. The output is not ever shown, even if it is an image file. Most of the time, there is barely an indication as to what just happened.

With today's operating systems, to make a 16:10 rectangle graphic and customize it in real time, you have to download a specific GUI application, and learn the five or six steps it wants you to take to do this. But if an operating system is designed properly, you open up an interactive command line, and type a few commands that you learned previously, and you have a window (or split frame) that opens showing you this rectangle, independent of any software application. Then, you have the option to save that shape as a file or modify it further with the same command line you used to make it. All of this would take place inside a kind of Swiss Army Knife terminal app. Something to note, interface controls can also be made to appear inside that split window frame of the terminal line if the command line makes that happen.

From here, there is no reason that the command line wouldn't be able to add interactive features to the rectangle, then export the result into a file format for later use. In this way, a "terminal" might blur the line between interactive command line and IDE.

When this type of setup, an interactive, graphical command line, is extended to the entire range of utilities a person would want, there will be less reliance on third-party applications to do very simple tasks. There will also be very little need to look up commands for rectangle sizing when there is a core set of conventions established for how a rectangle and its dimensions are treated for any function or program running inside the terminal.

For example, when resizing images with the command line, you must master all sorts of secondary arguments, consult the documentation for that image processing library to do something simple. But if you can operate on an image successively, as it is opened in a window, or split frame, in a terminal, this will create a much more fluid operating system experience. The commands you use to operate on that image are part of a base set that apply to all kinds of circumstances— not that single situation of modifying an image.

The command line should be a toolset at your side, not a collection of randomly-named programs that do their different things and ask you to know their specific ways of doing anything. In a command line, a person should be able to create a column of spreadsheet cells, place numbers inside them, and then request the sum, all without using the mouse. Then, from that point, the command line user can choose where to route the spreadsheet table: to a file, to an e-mail, or to the clipboard.

It is the extensible command line that will take advantage of an open source community, as the utilities can be added on that make use of the base set of commands mentioned earlier, which are established before the operating system is shipped.

This is an operating system command line terminal that knows what a pentagon is, and knows how to make it. It is the place where you convert units measurements, not a separate third-party app.

Some future scenarios:

- To get the word count of some copied text, type a command for generating a text container that appears inside the terminal window. A text container then shows up. Paste your document's text inside that text container, for getting a word count. Then type the command that counts words. (Alternatively, type a command that processes what is in the pasteboard, outputting a word count with the same command).

- Use FTP inside the terminal as if it is a separate application. A graphical FTP directory listing is opened in a new terminal window, activated by the interactive command line of the existing terminal window. An image is being generated and customized in yet another terminal window. After it you are finished working with it, you redirect its file output to the currently opened FTP directory, using the interactive command line.

- A rectangle of proportions 3:4 is generated with a width of 50pt. Next, it is repeated across a grid with spacing 10pt. Through commands given to the terminal, each rectangle has been filled with a grayscale color value along a linear scale. The interactive terminal allows adding a feature where clicking on a rectangle copies the hexadecimal color value to the system's pasteboard. There is a user-interaction file format for saving this grid of interactive rectangles to disk. It can be used later in software development.

The continual reliance on plain text

There is often an impulse to always preserve the ability to jump into a command line and edit the raw plain text of something, should something go wrong with a GUI application. This could be the reason that plain text has stuck around as the main medium of advanced computing.

But at the same time, this situation is a result of text editors themselves not being upgraded universally. If all terminal shells (bash, zsh, etc.) offer graphics capabilities, all text editors that run inside them can as well. Then, there won't be the persistent feeling that using plain text is keeping things free of potential pitfalls. The truth is, there are no computers incapable of displaying graphics these days. Therefore, all plain text editors should be able to use graphics. If it is the added layer of complexity brought by graphics that prevents this, this topic needs to be dealt with.

Code Layout Features Will Add Power to Plain Text Programming

We have shown how incorporating page layout features into plain text code will improve usage of screen space and enhance readability of code.

Since these commands affect only the areas of code they enclose, a programmer retains the option to apply them to only a certain portion of a file while leaving the rest of the code in its standard, plain text form. And, of course, the IDE can easily provide controls to turn off all of these layout instructions.

But also, with a small addition of commands emerges a multitude of opportunities to expand and improve the power of source code. What if a programmer could use a slider inside plain text code to change compile-time values? Use the --SLIDER(min:max) command:

// Add a slider that ranges from 5 to 120.

//

// --SLIDER(5:120)

var radiusOfCylinder = 55;

Other examples include editable tables for the tedious task that is editing dictionary and array variables, matrices for matrix math, and two-dimensional graphcs for things such as animation curves. New types of programming will be possible this way, as state machines and workflow diagrams will be possible to work with inside today's conventional plain text code, for the first time, in any major programming language.